Accounts of the French / Chickasaw War 1736

Bienville's Southern Force

This is our Fifth Musing which is a relation of, if not a companion of, the Fourth Musing. I say that because Bienville's plan was to have a northern force and a southern force attack the Chickasaw and Natchez villages simultaneously. The foundation documents within are Colonial French correspondences which originated in Louisiana or New France and were archived in Paris by Ministry of Marine. We will provide three correspondences and bits of others which describe Bienville's southern force campaign against the Chickasaw. The correspondences were translated by Mississippi Department of Archives and History in the 1920s and revealed in Mississippi Provincial Archives French Dominion (MPA).

As we progress, I will offer my opinions and comments of why the French/Chickasaw War of 1736 failed from the French perspective, especially Bienville's plan. Likewise, I will offer my opinions and comments relative to the Chickasaw and their English trader allies.

Bad Blood:

In the Fourth Musing we provided a link to Sieur de Bienville which we have upgraded via DCB/DBC (The Dictionary of Canadian Biographies) Mobile Beta Biography. Bienville was governor of Louisiana four times. He had good rapport with most of the Native Americans in the southeast even a faction of the Chickasaw. In 1736 he was approaching 55 years of age and complained of an illness which some have attributed to sciatica.

As Governor of Louisiana 1726-1732, Perier, Chevalier Etienne de Perier, may have been a fish out of water, literally. He began his naval career as a volunteer at age eight on board French escort vessels in the English Channel. By retirement he had achieved the rank of Lieutenant-General des Armees Navales. To say that his military career was distinguished is an understatement, as he was awarded Chevalier de St. Louis 1729, Commandeur de St. Louis 1755, and Grand-Croix de St. Louis 1765. Could Perier have been the only recipient of all three classes of the Orders de St. Louis? Hint, the Grand-Croix was supremely rare especially for a person without title. (I have since read that he was one of two Navy recipients of the Grand-Croix in the honors history!) Perier's brother, Chevalier Antoine-Alexis de Perier (Comte de Salvert), was awarded Chevalier de St. Louis 1738 and Commandeur de St. Louis 1756. Antoine de Perier also joined the French navy as a volunteer while young, age ten. He served in Louisiana 1731 as King's Lieutenant New Orleans and participated in Natchez War.

As Governors of Louisiana, Bienville and Perier shared two things. First, they believed the Chickasaw were the architects of the Natchez Massacre. In a letter dated April 1730 to Maurepas MPA I 118 Perier wrote, "It was the Chickasaws who conducted the whole intrigue." Bienville wrote to Maurepas in 1734 MPA I 243, "I shall spare no pains to accomplish the complete defeat of the Chickasaws."

Second, neither liked Diron D'Artaguiette as they expressed separately in letters to Maurepas, see MPA I 118, 237, 241. And to be fair, Diron D'Artaguiette did not like them, see MPA I 249. Bienville for his part held the trump cards and did not include Diron D'Artaguiette in his southern campaign planning (from available correspondences) or execution. But the Governors were not alone expressing their dislike of Diron D'Artaguiette, Regis du Roullet an officer who recorded a long tour of the Choctaw villages wrote Maurepas about Diron D'Artaguiette's lack of personal assistance and his dislike by the Choctaw chiefs, MPA I 173, 174. Coincidentally and previously, Regis du Roullet served under Diron D'Artaguiette at Fort Toulouse as an ensign then under Sieur de Lusser at Fort Conde as a lieutenant. He left Louisiana after nine years of service, see MPA I 17.

During his last term as governor beginning 1733 Bienville attempted to right the wrongs (from his POV) of the previous governor Perier's Indian policy. In the two years leading up to the French/Chickasaw War of 1736 he increased his attention of the neighboring Choctaw who were being wooed by the English traders out of "Carolina" and/or "New Georgia", see MPA I 183, 190, 233, 254, 270, 277.

To be fair to Bienville there were extenuating issues affecting Louisiana other than Indian relations. A hurricane had devastated the coast in August 1732 creating food and shelter shortages in Mobile and New Orleans. The summer and fall of 1735 brought a severe drought. There was a lack of hard currency; consequently prices had inflated several fold. There was a shortage of imports and supplies from France: replacement soldiers, food, munitions, trade goods and presents for the Indians. There was a perceived lack of support from the King. The situation was dire and no time to gather supplies for a war.

As for Indian relations, compared to the English, prices for French trade items were higher and their quality poorer. Deer hides constituted most of the Indian trade. The English system for ranking the trade of deer hides was superior to the French. The Indians knew all of this. They had complained often for years. It was especially apparent to the Choctaws who were Mobile's significant neighbor and defensive buffer against the Chickasaw and their English traders.

Background:

Immediately following the 1729 Natchez revolt including the massacre of French soldiers, most male colonists and a few women (some pregnant) at Fort Rosalie, the French attempted to exterminate the Natchez. After two successful military engagements against the Natchez in 1730, the French witnessed one then two Natchez groups take refuge with the Chickasaw, see Paper 1 The Decades and the Villages 1720-1730 and 1730-1740 and Table 1. (Note: There were several Natchez groups, one moved west to near the Caddo tribe and another moved east. Eventually the Natchez living with the Chickasaw moved to the Creek and Cherokee Indians.) Shortly after 1731 the Natchez village was situated on the eastern edge of the northern group of Chickasaw villages as documented by French maps, see Paper 1 Figure 7 (village labeled Tchikoulechasto) and Paper 1 Figure 9 (village labeled Natchez). When Bienville became Governor again, he demanded the Chickasaw turn over the Natchez. The Chickasaw refused. The Natchez had embarrassed the French, and the Chickasaw had mocked them. The French reputation in Louisiana and New France was in shambles. Bienville had to restore it, at all costs.

Setting the Table:

After his return to Louisiana, Governor Bienville spent 1734 and 1735 trying to rebuild relationships with Indians tribes, starting with the Choctaw. (For the reader's knowledge: The 1700s Choctaws were located in what is now east central Mississippi and less so in Alabama and Louisiana. Politically and geographically there were two divisions, eastern and western. Compared to the Chickasaw the Choctaw were very populous and occupied more than 32 villages.) The French conducted Indian affairs in Mobile (rarely New Orleans) at Fort Louis then Fort Conde de la Mobille because the Mobile River afforded access to the Tombigbee River which coursed near the Choctaws and Chickasaw villages. Other Mobile River tributaries included the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers which flowed by Fort Toulouse and the villages of the upper and middle Creek confederacy. Here is a link to French Louisiana Mobile and d'Anville's 1732 map of Mobile Bay and Mobile River https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Mobile,_Alabama#/media/File:Mobile_in_1732.jpg.

In addition to Fort Conde at Mobile the French had several forts which factored into the Chickasaw War of 1736. Upstream of New Orleans on the Mississippi river there was Fort Rosalie which was built in 1716 and which was rebuilt by 1731 after the Massacre of November 1729. It was situated overlooking the Mississippi River at present day Natchez, Mississippi. Further north Arkansas Post was built on the Arkansas River near present day Gillett, Arkansas. It was founded in 1686 by Henri de Tonti and rebuilt many times due to river flooding. A major expansion was made in 1731. Further upstream near what is now Memphis was Fort Prudhomme which was established by LaSalle in 1682. It was never used afterwards. To the Colonial French Fort Prudhomme was also known as Ecorse a Prudhomme. The exact location of Fort Prudhomme is not known. Continuing upstream the French established Fort Chartres in 1720. The fort is about 40 miles south-southeast of what is now St. Louis. The area around Fort Chartres was called the Illinois settlement, and it became a successful agricultural and mining colony. Several Indian tribes resided nearby. East of Fort Chartres was Fort Vincennes founded by Sieur de Vincennes in 1731-2 on the Wabash River. Much further south and west was Fort St. Jean Baptiste on the Red River. Informally this French fort was called Fort of the Natchitoches, and it is located near present day Natchitoches, Louisiana. These forts and settlements supplied the forces and materials for the French in the French/Chickasaw War of 1736.

Prior to 1736 the Chickasaw villages had experienced change at the hands of the French. James Adair described the Chickasaw village locations in the year 1720 although he first lived with the Chickasaw in 1744, see Musings Where Was James Adair's Trading House? Adair had traded and resided with other southeast tribes since 1735; he knew that in 1722/3 there were French and their Indian allied (principally Choctaw) raids against the Chickasaw. The greatest French success was an attack on the village of Yaneka, see Paper 1 Figure 1. Yaneka was remote and distant from the other Chickasaw villages. In addition it was vulnerable to the south, the direction of the Choctaw. This raid was described in Paper 1 The Decades and the Villages 1720-1730. The French were decisive largely because they had equipped the Choctaw with guns and offered a lucrative bounty for Chickasaw scalps. The result was a number of Chickasaw dead and prisoners who were sold as slaves. The Chickasaw survivors abandoned Yaneka and a number moved to South Carolina under British protection.Paper 1 Table 1 indicates the name Yaneka disappears from the village names in the home land (except a Memoir of 1755 which inferred that some Yaneka peoples or their heirs may have moved back). The de Cresnay map of 1733, see Paper 1 Figure 6, does not locate Yaneka as a village. Likewise the De Batz map fails to indicate Yaneka as a village in 1737, see Paper 1 Figure 8. The surviving Chickasaw peoples of Yaneka had left the Chickasaw villages.

I take a moment to introduce the full de Cresnay map of 1733, courtesy of https://da.mdah.ms.gov/series/maps/detail/191241. Baron Henry de Cresnay was King's Lieutenant in Mobile. In 1732 while acting as Governor he made the Choctaw war chief Red Shoes a medal chief. The 1733 map is furnished via Mississippi Department of Archives and History and was published in the Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73. This second link is courtesy of the Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections, https://cdm16044.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15099coll3/id/1262. Note the map is regional to southeast portion of US and is in French. North is up the page. The locations on the map are not exact geographically rather they are relative. Note on the lower border "Baye de La Mobille" or Mobile Bay and "Fort Conde" or Mobile. Note to top "PAYS DES CHICACHAS" and in the middle "PAYS DES TCHACTAS" or country of Chickasaw and Choctaw. The Chickasaw villages' layout is approximate geographically, but the creek locations in their vicinity are representative. Rivers are shown as solid line, and trails are dashed. The trails shown are in all likelihood major trails but there were many other trails. These trails were well used by man and horse. We will refer to this map many times. Ecorse a Prudhomme, the bluff where Pierre D'Artaguiette's northern force rendezvoused, which was prevalent in Fourth Musing, is outside of the map's coverage.

The Lay of the Land:

The Chickasaw controlled a vast territory from their villages with a focus near present day Tupelo. To the North they claimed all land to Nashville and hunted annually to the Ohio River. To the south they had a well known border with the Choctaws: beginning at Tibbee Creek south of present West Point moving West-Northwest towards St. Francis River to the Mississippi River. The Chickasaw claimed all lands north of that line to the Ohio River including the Mississippi River and everything and everyone that plied it.

The First Blows:

The 18th century French and British frontier of southeastern North America never experienced an extended peace, especially near the Chickasaw. As can be read in Paper 1 The Decades and the Villages 1730-1740, the Chickasaw raided the Wabash River and Bienville encouraged various northern Indians to retaliate. He had a bounty on Chickasaw scalps that provided incentive to northern and southern Indian tribes. In 1734 a French/Choctaw raid attacked the forts of the village of Chatelaw (Tchichatala, see Paper 1 Table 1 or Shatara per Adair Paper 1 Figure 1) on Coonewah Creek and reportedly took 46 Chickasaw scalps, see Paper 1 Figure 7 and MPA I 245.

From New Orleans on August 20, 1735 Bienville writes (MPA I 264) to Maurepas,

"I am informed that two Illinois parties marched this last winter a short distance from each other against the Chickasaws; that the first captured twenty women and children from the enemy and the second sixteen and a man whom they burned; that the three villages are going to march en masse this autumn, and I do not (f. 153 v.) doubt that Mr. D'Artaguiette (Pierre) will send several Frenchmen with them."By using Indian allies from the north of Louisiana to raid the Chickasaw Bienville increased the pressure on the Chickasaw (to turn over the Natchez).

Bienville was not going to wait on peace with the Chickasaw, he began planning his war against the Chickasaw, the Natchez and the English traders living among them, see MPA I 277. He formulated a two prong coordinated attack. He would lead a southern force from Mobile which would travel by boat up the Mobile and Tombigbee Rivers to near the Chickasaw villages. A northern force would leave Fort Chartres under the direction of Commandant at Fort Chartres Major Pierre D'Artaguiette (the younger brother of King's Lieutenant at Mobile Diron D'Artaguiette) which would travel by boat down the Mississippi River to the Ecorse a Prudhomme and thence overland to the Chickasaw villages. Both forces would include French troops, French militia (trained locals living about French forts also called habitants) and Indian allies. Bienville's force also included Swiss troops and Negroes. Bienville's plan was for the forces to attack the Chickasaw and the Natchez in March 1736.

Bienville's initial order to Pierre D'Artaguiette was to meet him March 10th or 15th 1736 at Ecorse a Prudhomme. D'Artaguiette was to man his force selecting French troops from Fort Chartres and Fort Vincennes. The militia would be selected from the French settlers living near the forts. The numbers of troop in the force were not to diminish the capabilities of Fort Chartres or their environs. In addition, Indians of the Illinois settlement including Cahokias and Michigameas were to join the Northern force under leadership of Sieur de Monchervaux; likewise Iroquois and Miamis under the leadership of M. de Vincennes and Arkansas Indians under Sieur de Grandpre from Arkansas Post were to meet at the Ecorse a Prudhomme. Since the Ecorse a Prudhomme was in Chickasaw territory, a temporary palisade was to be erected to give cover and protect the boats and supplies.

Materials for the Northern campaign had to be assembled. Bienville ordered Lieutenant Sieur de Coulange, the Commandant of the Arkansas Post, to have 1,700 pounds of powder transported to Fort Chartres via boat (bateaux were used to transport large volumes and weight while pirogues normally carried a few men and limited supplies) on the Mississippi River. When the powder did not arrive at Fort Chartres, Pierre D'Artaguiette sent Lieutenant Ducoder to Arkansas Post by boat to retrieve it. On the return trip Ducoder landed to rest his party in Chickasaw territory and was attacked by a large group of Chickasaw and Natchez who were following his flotilla. His boating party was killed; Ducoder was captured as was the powder, see MPA I 268-9. Bienville confirmed the loss to Maurepas in a letter dated August 20, 1735,

"In the meantime I received a letter from Sieur Ducoder written from a Chickasaw village which informed me that when he was half-way between the Arkansas and the Illinois he had put into the land to rest and refresh his crew; that during that time he had entered the woods to see if he could discover any tracks; that a little while afterwards he heard a discharge of more than two hundred gunshots accompanied by shouts which left him no doubt that his detachment was attacked; that he ran at once toward his boat where he was seized by several Indians; that the others were occupied either in plundering or in tying a sergeant and a soldier who alone remained alive. He informed me that this party composed of two hundred and forty Chickasaw and Natchez men was on the march to go and carry away the women that the Illinois had taken from them a short time before, or to get vengeance for this act; that they had been following him for several days to take him by surprise, but that hitherto he had always kept to the other side of the river; in fact if he had continued to observe this precaution, which was quite natural, he would have escaped from their pursuit. He adds that after these Indians had divided among themselves the cargo of the boat they abandoned the purpose of vengeance which had made them leave their villages the journey to which they resumed, and that they arrived there without having received any insult. This news made me decide to send immediately to the Illinois a boat loaded with powder to replace that which the enemies have taken from us, accompanied by all the voyageurs who had come down the river, so that this convoy is composed of about eighty Frenchmen and forty negroes and is in a position to fear nothing from our enemies."With the capture of the powder, the Chickasaw had just won the first battle in the French/Chickasaw war. Ironically the captured powder would be used against Major Pierre D'Artaguiette. (What was the significance of 1700 pounds of black powder? If the Chickasaw had 500 warriors with flintlock guns, figuring 70 grains of black powder per flintlock shot and 7000 grains per pound, then each warrior would have 340 flintlock shots from the captured powder. Normally the Chickasaw would have received powder from Charleston, South Carolina or Savannah, Georgia via English traders' train of pack horses.) Bienville investigated why Coulange had not obeyed his order to transport the powder to Fort Chartres. In MPA I 267 he wrote that he discovered that Sieurs Coulange (bio Forth Musing as Coulanges), Grandpre (bio Fourth Musing) and Laloere Flaucourt (Louis Auguste de la Loere Flaucour clerk at Fort Rosalie and principal clerk and judge Mobile and Fort Chartres) had formed a trading company outside of their duties. For his disobedience Coulange lost his command, was demoted to ensign, and was imprisoned at Fort Chartres for six months.

The English traders who lived and traded with the Chickasaw became active among the Choctaw, too much so for the French. These traders didn't have the convenience of river to travel to and from Charlestown (Charleston) and New Georgia (Savannah). Instead they transported deer skins and trade goods via trains of pack horses and mules. In 1733 the English traders began showing up at rivers (Kaapa (French name for Cahaba River) and Tascaloosa (Black Warrior)) just east of the eastern Choctaws MPA I 187, 231. Worse, several key Choctaw chiefs, Alibamon Mingo and Red Shoe, reciprocated the English interest, see MPA I 233, 255, 278 and MPA III 673. It was rumored that both of these chiefs went east with English traders! See MPA I 277, 278. The French feared they had gone to Charleston or Savannah. Bienville proposed to Maurepas in 1735 that a post be established on the east side of the Choctaw to buffer the Choctaw and thwart the English traders, MPA I 258. Specifically he suggested Fort Tombekbe be built on the Tascaloosa River. He wasn't the first in Louisiana to suggest that location. Regis du Roullet, who toured the Choctaw Villages and recorded a journal including chiefs, distances, warrior strength, etc., in 1731 (MPA I 149) wrote Maurepas that the English were trading goods on the Tascaloosa River (Black Warrior), see MPA I 187. Father Beaudouin (Michel Baudouin per DCB/DBC Mobile beta), a Jesuit priest and 20 year missionary living with the Choctaws, suggested the site Tascaloosa in 1732 to Salmon, see MPA I 163. (Salmon was Edme-Gatien de Salmon who was Commissary of Louisiana and Superior Court Judge). Diron D'Artaguiette moved a trader to Tascaloosa in 1731 and suggested to Maurepas in 1734 that a post be located there, see MPA I 185. In a September 1735 letter to Maurepas MPA I 274 we learn that the construction of the post at Tascaloosa is part of Bienville's Chickasaw campaign,

"My first concern … will be to send men to carry out the establishment of the Tascaloosas which I have been planning for a year. This establishment …will facilitate our trade with the Choctaws of the eastern part from which it will be only twelve leagues distant, and will serve us a depot for the campaign of next spring."

Given the friction with Diron D'Artaguiette, Bienville probably listened to Father Beaudouin regarding the need and location for establishment of a fort.

Bienville reported to Maurepas that by February 1736 he had sent Captain de Lusser to Tascaloosa to establish the post to receive his army enroute to the Chickasaws, see MPA I 278.

As we shall learn, the post was not established at Tascaloosa. Bienville's plan would change at the midnight hour of his campaign.

Bienville's Southern Campaign Planning:

Bienville's plan to advance his army to the Chickasaw villages evolved over several years. He considered the season to conduct the campaign, possible routes of travel, means of travel and weather.

In August 1733 Bienville wrote Maurepas of his developing Chickasaw strategy,

"Besides the spring is not the season favorable for this expedition. Autumn is the only suitable one, because then by living at the expense of the enemy, one can remain in the field a long time, and if one does not destroy them totally, one reduces those who are left to the necessity of living by hunting and to the risk of soon becoming the prey of all the nations."See MPA I 199.

Bienville has concluded that autumn is the time to attack the Chickasaw as their corn and crops will be ripe. The French can choose to either live off their crops or destroy them so that the Chickasaw cannot use them.

MPA I 249 September 1734 Diron D'Artaguiette wrote to Maurepas that Bienville had written asking him to delay a Choctaw raid until fall,

"He wrote to me to delay them, if it was possible, until the month of September which is the time of maturity for corn and other large cereals, because we should find provisions for the subsistence of the army in the country of the enemy himself."Bienville has concluded that the early fall was the time of year to attack the Chickasaw? Read on.

In MPA I 273 on September 9, 1735 Bienville wrote Maurepas that he has a change of mind about the right season for the campaign,

"I am going to work seriously, then, at the preparations for this campaign which will not take place until toward the month of February, the most favorable season for the plan that I have of sending the expedition by way of the Mobile River, inasmuch as in the other seasons the water is too low to float pirogues. By this route our force will arrive within twenty leagues of the Chickasaw without being very much fatigued and the transportation of munitions of war and provisions and utensils will be effected more conveniently and at less expense. Furthermore, the French, having had time during the winter to recover the strength that the heat of summer and the diseases of the summer have made them lose, are consequently stronger in the spring and in better condition to sustain the fatigues of this campaign."

The letter is dated September, and he is two months distance from the Chickasaw by whatever means of travel. So he would have to wait a year for the next autumn to be present before the Chickasaw. Instead of waiting, he changes the correct season to late winter and early spring and decides that boats will convey his army via Mobile and Tombigbee Rivers. It will take at least two and a half months for couriers to reach Pierre D'Artaguiette at Fort Chartres from New Orleans. Even with couriers travelling up the Mississippi River in a shallow draft pirogue. Does Bienville have time to tell Pierre D'Artaguiette of his change in plans?

In a letter dated February 10, 1736, see MPA I 278, Bienville admits to Maurepas that the time for his campaign was not quite right,

"I formed at that time the resolution to march against the Chickasaws as soon as the river which leads to their country could be navigated … in the journey I have just made to Mobile I learned that the water would not be high in that country until toward the months of April and May."

Bienville delayed his campaign again … to April or May! What about Pierre D'Artaguiette and the northern force? What about the all important coordinated attack on the Chickasaw villages? Bienville knows that he is at least two months from Mobile to the Chickasaw villages by boat and foot. And March is when he is to meet Pierre D'Artaguiette at Ecorse a Prudhomme for the two pronged attack. How does he know the river can't be navigated? There was a long drought during summer of 1735, but it hasn't been mentioned in recent correspondences. What is going on? Why the delay? What is Bienville hiding from Maurepas? (Tongue in cheek, in 1736 Bienville knows a good fortune teller in New Orleans who can predict the weather in North Mississippi? Please tell the weather prognosticators.)

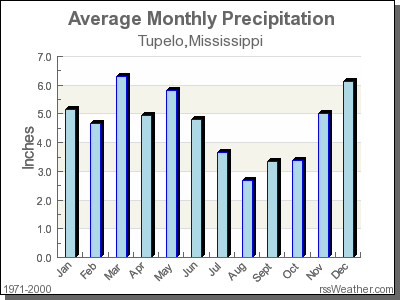

There is rationale to Tombigbee river flow, rainfall and months of the year. The graph shows average rainfall in inches for the months of the year at Tupelo for several recent years.

Tupelo is within the Tombigbee River drainage basin so the record is applicable. Of course, Bienville had no such data but he should have known that August, September and October were the driest rainfall months while May, December and April were the wettest. Of course, rainfall within the river basin contributes to river flow. I have had numerous experiences of seasonal multi-day camping and boating excursions within the Tombigbee River watershed near Amory, Ms. The river is very responsive to rainfall both rising and falling. In Bienville's case if he has large bateaux similar to those used on the Mississippi River (40 feet long, 9 feet wide and 4 feet of draft) then I agree he will have issues navigating the Tombigbee River at low flow upstream of Plymouth Bluff near Columbus Ms. Why the need for large bateaux? He planned to have artillery. And he knew that muddy Indian trails would make the use of carts for transporting heavy loads like artillery, powder and ball almost impossible during the winter and early spring. Bienville provides more information on the artillery in the First Correspondence below.

There is rationale to Tombigbee river flow, rainfall and months of the year. The graph shows average rainfall in inches for the months of the year at Tupelo for several recent years.

Tupelo is within the Tombigbee River drainage basin so the record is applicable. Of course, Bienville had no such data but he should have known that August, September and October were the driest rainfall months while May, December and April were the wettest. Of course, rainfall within the river basin contributes to river flow. I have had numerous experiences of seasonal multi-day camping and boating excursions within the Tombigbee River watershed near Amory, Ms. The river is very responsive to rainfall both rising and falling. In Bienville's case if he has large bateaux similar to those used on the Mississippi River (40 feet long, 9 feet wide and 4 feet of draft) then I agree he will have issues navigating the Tombigbee River at low flow upstream of Plymouth Bluff near Columbus Ms. Why the need for large bateaux? He planned to have artillery. And he knew that muddy Indian trails would make the use of carts for transporting heavy loads like artillery, powder and ball almost impossible during the winter and early spring. Bienville provides more information on the artillery in the First Correspondence below.

Bienville's Southern Campaign Execution:

For the benefit of the reader we will provide copies of the translated French correspondences concerning the accounts of the campaign and its immediate aftermath. The correspondences regarding the French/Chickasaw War are from the five volume set of Mississippi Provincial Archives, French Dominion (MPA). In 1906 Mississippi Archives and History communicated a desire for documents from the French Archives of the Minister of the Marine in Paris. Selection criterion was developed, and documents were copied and sent to Jackson. Selected documents were translated by A. G. Sanders and overseen by Dunbar Rowland. The first three volumes were published Volume I 1927, Volume II 1929 and Volume III 1932. These documents are available at the Lee County Public Library. Additionally, this link from the HathiTrust Digital Library and the University of California allows the reader to access a pdf of MPA Volumes I, II, and III, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102320441. To my knowledge MPA Volumes IV and V are not available by pdf.

The First Correspondence:

As you read the correspondences, keep in mind we are reading Bienville's letters addressing the implementation of his plan. Bienville in September 1735 assures Maurepas,

"I am going to work seriously, then, at the preparations for this campaign,"MPA I 273.

For the first account we have selected a correspondence from Bienville who is in the field at the Camp of Tombekbe (spelling varies) enroute to the Chickasaw. Maurepas is to be the recipient of the letter. Why is Bienville at the Camp of Tombekbe and not the Fort to be built at Tascaloosa? All of the previous correspondence even as late as September 1735 (previous) state the post is to be located at Tascaloosa. Why the late changes? Does Bienville explain the change in the correspondence? Surely there are no other changes? Surely.

From MPA I 294 . . .

FROM BIENVILLE TO MAUREPAS

(From Ministry of the Colonies, C. 13, V. 21, General Corre-spondence of Louisiana, pages 168 to 170; copy Vol. XXIII, pages 240 to 243.)

My Lord:-

As I earnestly wished that your Lordship should be in- formed by the return of the Gironde of the result of my expedition against the Chickasaws, about which I have already had the honor to write you at length by the ves- sel of Rateau, I had agreed with Mr. Salmon to urge (f. 168 v.) Mr. De Villers to wait as long as he could for the news of my return and for my letters for France, but the contrary winds so greatly interfered with the trans- portation of the troops and the provisions from New Or- leans to Mobile that I was not able to depart until the first of April, that is to say a month later than I had expected. Considering also that there are few provisions at New Orleans, where I could not be until the end of June, I am deciding to write to Mr. De Villers to leave at the regular time, because, having found a strong cur- rent thus far, I have no reason to hope to find less until the landing.

The almost continual rains have made me take twenty- three days to go to this bluff, which, as your Lordship (f. 169) may notice, is not the one where I had expected to make the settlement.

The sentiment of the trustworthy Choctaws has made me abandon the idea of establishing a post at Tascaloosa, and in fact although that is a very fine place, this one which is fifteen leagues farther up has great advantages over the other. We are here situated between the two roads that the English take to go to the Choctaws and one day's journey from the villages of this nation that are in the eastern part.

As I find myself very busy here I am postponing until my return the honor of replying to my lord's despatches of the dates of the thirteenth, twentieth and twenty- seventh of last September, of the fourth and eleventh of last October, and I am sending this one to New Orleans by some boats that I am sending back there, not thinking them suitable to ascend the river of the Chickasaws (f. 169 v.) where the water might suddenly go down, al- though it is very high at present. I shall also send you on my return the plan of the fort that I have had drawn up during my stay here, where all the chiefs of the Choctaw villages without exception have come to assure me of their attachment to the French with whom they say that they wish to die this time. I have had munitions given to them and they have promised me to go as soon as I do to the land of the Chickasaws where we have desig- nated a place of meeting.

Several war parties that have brought me scalps have told me that they had seen large trails which make them think it is assistance sent to the Chickasaws by the Eng- lish. I think rather that it is Mr. D'Artaguette who, (f. 170) hurried by his Indians and having arrived before me, did not wish to return without striking a blow.

I am with a very profound respect, My Lord,

Of Your Lordship,

The very humble and very obedient servant,

Bienville.

From the Camp of Tombekbé, May 2d, 1736.

The reader will note that the spellings of proper nouns differ and vary, especially D'Artaguette, Tascaloosa, Tombekbe, Liviliers and de Villers. In the remaining correspondences the same will be true.

The Gironde and Rateau were two of several French ships which dealt in Colonial commerce and transported correspondences to and from France and its colonies.

Mr. de Liviliers was Charles Petit de Levilliers 1698-1738 a Lieutenant in 1720 Colonial Louisiana and promoted Captain 1726. While he survived his wounds from the Chickasaw campaign, he died from wound received in a duel with another officer, Barthelemy de Macarty Matigue at Fort Chartres. His younger brother was Pierre Louis Petit de Levilliers de Coulanges (Sieur de Coulanges) 1699-1736 who was commandant at Arkansas Post, failed to transport the gun powder to Fort Chartres and died in Pierre D'Artaguiette's northern force, see Fourth Musing.

What is apparent in this correspondence is that it is rife with Bienville's complaints: contrary winds, few provisions, strong current and almost continual rains. Didn't Bienville plan for any of these changes? They are not contingencies. Wasn't he just explaining to Maurepas that he needed high water to access the Chickasaw? Bienville admitted that he was late by a month or more, and it was not his fault?

What about the change of location of the fort from the Tascaloosa to the Tombekbe River? Bienville first proposed a fort or establishment to Maurepas on the Mobile River April 1735 MPA I 258. Both the Tascaloosa and Tombekbe Rivers are tributaries of the Mobile and the exact location was not certain. In September 1735 Bienville defined the proposed location to be on the Tascaloosas, see MPA I 274. He admitted to Maurepas that he had been working on the plan for a year. With so much energy advanced to that location, why move it during a campaign? Bienville offered an excuse. It was the Choctaws who suggested the change of site to the Tombekbe. But he pointed advantages to the new site: it was closer to the eastern Choctaw villages (the Tascaloosa site was 15 leagues from the eastern Choctaw towns and the Tombekbe location was one day journey or about 7 leagues). The new location would interrupt the English trader trails to the Choctaw from Carolina and Georgia. But why weren't the Choctaws consulted about the proposed location months before? Bienville had several French in the Choctaw villages' full time, and it had been more than a year since Bienville proposed the Tascaloosa site to Maurepas. The change of Fort locations is just a white lie, right?

The proposed and new fort/post locations may be seen on the Baron de Cresnay map of 1733. The proposed location was on the "Tascaloussa R" at "Ecor Blanc" while the new post Fort Tombekbe is on the "Riviere Des Chicachas" at "Grand ecor blanc". Fort Tombekbe is now owned by the University of West Alabama, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/m-7367.

The most troubling part of Bienville's letter concerns his "D'Artaguette" statement. … that the large trails found by scouts he believes are signs of Pierre D'Artaguette "striking a blow" before returning (presumably to Fort Chartres). In Fourth Musing we noted there are two versions of Bienville's final order to Pierre D'Artaguiette. Bienville in his account stated the final order was "to take his measures accordingly" MPA I 312; however, the acting commandant at Fort Chartres de la Buissonneire and his principal clerk Delaloere stated in letters that the final order was "to retard his march, and wait for him in order that they might strike together against the Chickasaws and Natchez," see Fourth Musing Indiana Historical Society Indiana's First War p. 121.

What was Pierre D'Artaguiette to do if he received Bienville's order to take his measures accordingly? D'Artaguiette received the order per Bienville just before he arrived at the Chickasaw villages. He had no other choice but to attack.

What was Pierre D'Artaguiette to do if he received the order to retard his march and wait for Bienville? Again the order was received just outside the Chickasaw villages. If this was the final order it should have been received at least three weeks earlier or before he left Ecorse a Prudhomme.

Whichever final order was sent…the Northern force was doomed.

But why would Bienville tell Pierre D'Artaguiette to take his measures accordingly? Bienville's entire plan was to coordinate the attack of the northern and southern forces! The fault is Bienville's. His issues are developing and implementing a poor plan.

What other excuses will Bienville find for his plan and campaign's failure?

The Second Correspondence:

In this correspondence Bienville gives more insight into the campaign of the southern force. He introduces more of his French officers, calendar of events, decisions, order of battle, disappointments and issues, the later of which he states that he has no control.

When you read this, perhaps a second time, imagine that you are Maurepas and the impressions the letter gives you…two months and 4,700 miles away.

From MPA I 297 . . .

FROM BIENVILLE TO MAUREPAS

(From Ministry of the Colonies, C. 13, V. 21, General Corre-spondence of Louisiana, pages 188 to 203; copy Vol. XXIII, pages 247 to 275.) Abstract of the journal of the Chickasaw campaign.

My Lord:-Before we provide information relative to proper names in the correspondence and before we discuss the battle, let's address the campaign scheduling issues Bienville mentioned in the Second Correspondence.

The departure of the King's vessel which is to set sail from the Balize in four days leaves me too little time to be able to render your Lordship a very detailed account of the events of the campaign against the Chickasaws, from which I bring back, moreover, my health so im- paired by (f. 188 v.) the hardships and fatigues that I have undergone in this journey that I should be incapable of the application that this detail calls for. I shall con- tent myself then, in order not to leave your Lordship in ignorance of the principal circumstances of my enter- prise, with sending you an abstract of the journal that I have kept from the time that I planned it. If the outcome has not corresponded to the measures that I had taken to assure its success, I flatter myself that your Lordship will not be at all surprized at it when he is informed of the disappointments that I have had to contend with, disap- pointments whose result it was impossible to avoid since it was not possible to foresee them and since I lacked means to remedy them even if I should have foreseen them. The blow struck at Sieur Ducoder by the Chickasaws having deprived me of all means of finishing the war by an agreement, and (f. 189) the fear of seeing the Choc- taws continually solicited by the English to take their side made me decide to resort to arms as the only means that I had left to get out of this affair honorably. To succeed in it I laid my plan before the Choctaws when they came to see me at Mobile, and when they had given me a prom- ise to support me in this expedition I despatched in the month of December a pirogue to Mr. D'Artaguette to carry him orders to assemble all the forces of the Illinois and to lead them against the Chickasaws at the end of March with large supplies of provisions. I then was ex- pecting to go there at about that time, but the necessity in which I found myself of waiting for the arrival of the King's vessel for the salt-provisions of which we were in want and for the mortars that I had requested made me lose the entire month of February. The vessel did not arrive until the end of this (f. 189 v.) month and brought no mortars at all. I was conscious of the extent to which the negligence that was shown in this matter at Rochefort would be prejudicial to the success of my undertaking, but I could no longer withdraw from it without running the risk of losing the confidence of the Choctaws. How- ever I learned at Mobile that the preparations upon which I had agreed with Mr. De Salmon before my de- parture from New Orleans were proceeding very slowly and that the boats that I had ordered for the month of October had not been furnished by the contractors on the fifteenth of January. I left at once for the capital in spite of the inclemency of the season. I despatched on arriv- ing there a second courier to Mr. D'Artaguette to order him to delay his departure from the Illinois until the end of April.

In the meantime I had livelier work done on the prep- arations, and when I saw them at the point where I wished them I withdrew (f. 190) from the garrisons of the Natchez, the Natchitoches and the Balize all the offi- cers and soldiers that I could withdraw without stripping these posts too much. I formed a volunteer company of young men and of voyageurs who were then at New Or- leans and another of militia from the citizens who were not married. I had them depart for Mobile. Likewise I had the troops march there in proportion as the boats were ready. I set out finally on the fourth of March after having sent by way of the lower river the large boats laden with supplies and utensils, and I left behind me only four French companies which I ordered Mr. De Noyan to lead to Mobile as soon as the rest of the boats were completed. These troops, delayed by the winds, did not arrive until the twenty-second, and on the twenty- eighth there arrived a large boat laden with rice which had left New Orleans (f. 190 v.) before me and which on account of the bad weather had lost half of its cargo. This misfortune obliged me to have more biscuits made to replace this rice, but as this replacement would have greatly delayed my departure from Mobile, I sent some bakers to our new establishment of Tombekbé through the Choctaws, and I wrote to Mr. De Lusser who was in command there to build ovens and to use for biscuits all the flour that he had left. At last having set out from Mobile on the first of April we arrived at Tombekbé on the twenty-third. My lord has seen in the letter that I had the honor to write him from there with the date of the second of May how greatly I had been delayed by the currents and by the rains that were so frequent that I had protected my provisions only by a miracle. I was even obliged on my arrival to have work done on the ovens because the clay of the country, being too heavy, cracks in the fire and Mr. De Lusser after many attempts had only one that was in good condition. We made three others by mixing the clay with marl and sand, but all that could only furnish us fresh bread during our stay and give us enough for three days when we left. While waiting for the arrival of the Choctaw chiefs who were to come and join me there I held a review of the troops, the list of whom is enclosed herewith. I with- drew from them the garrison for the post and the com- pany of grenadiers which was to be commanded by Sieur de Hauterive, the oldest of the captains. I also formed a company of forty-five armed negroes to which I gave free negroes as officers. On the twenty-sixth of April the first Choctaw chiefs arrived in the evening, and of this num- ber was Alibamon Mingo. The next morning I (f. 191 v.) received them. They all began their speeches with great protestations of attachment to the French and ended them all by asking me for munitions, vermilion and provi- sions.

I replied to them in regard to this last article that from the time that I had notified them that I was going to war I had also told them that those who wished to follow me should bring provisions for themselves because I could carry enough only for the French, but that I would have powder, bullets and vermilion given to them, and with this they seemed satisfied.

I learned on the same day from Sieur de Léry who came from the Choctaws that several villages that had set out on the march had returned home because of a rumor which was current in the nation that the French who were going to descend from the North (f. 192) were also going to make peace with the Chickasaws, and that our intention was to attack all together the Choctaws who had followed us. I at once sent out Sieur de Léry to un- deceive them, and he was followed by several of those who had already arrived.

On the twenty-eighth the Great Chief of the nation ap- peared with several others in the number of whom was Red Shoe who spoke in the same terms of affection as those who had already made harangues. I knew how- ever by letters from the Natchez that since my depariure from New Orleans he had burnt i under the cannon of the fort the cabins of the Ofogoulas who had taken refuge there, and that Sieur de St. Thérèse who had remained as commandant at this post had been obliged to have a can- non fired which had made him retreat, but as he did not (f. 192 v.) speak of it at all, I was willing to know nothing about it, also not thinking the time suitable to reproach him.

The Great Chief spoke at the end of his harangue of the rumor that was current in his nation of our pretended plot against it, and added that one of their parties had seen in the direction of the North a great French trail and that it was the people of the North who had gone to the Chickasaws.

I explained to him thereupon the orders that Mr. D'Ar- taguette had had to descend with the northern nations to join me and attack our enemies together, and that if it were he who had made this large trail, he had apparently not received a courier that I had sent him to delay him; but that in case he arrived first we should have news of him. The Great Chief seemed reassured (f. 193), and I made him, as I did to all those who spoke to me that day about getting provisions, the reply that I had made the preceding day. I ended the meeting by having them told that when the rest of the chiefs arrived we should have a conference all together about the route that we should take and about the place of meeting for all the warriors. On the same day I had the fort of the post laid out, and although it rained almost continually I had men work at unloading several large boats loaded with provisions, in order to send them back to Mobile for fear that I should not find enough water for them while descending. The river in the meantime was high, but I knew that only a few days of fair weather were enough to make it almost dry.

(f. 193 v.) On the twenty-ninth the chief of the Chick- asawhays arrived with the rest of the chiefs except two or three who being sick sent warriors in their places. They made harangues in the same terms as the others and I put them off also until the general conference. In the meanwhile I had powder, bullets and vermilion distrib- uted to all.

On the thirtieth I assembled the council of war and we sentenced to death a sergeant and a soldier of the com- pany of Lusser guilty of conspiracy against the lives of the officers of the post and of plotting desertion. The reports of their trials which were held on the preceding days by Major Chevalier de Noyan will be sent to your Lordship on the first opportunity. The Swiss also held a council and convicted two of their soldiers as accomplices of the sergeant (f. 194). On the first of May I conferred with the assembled chiefs and they agreed to go with their warriors in fourteen days to Octibia, a little river that forms the frontier between the Choctaws and the Chick- asaws forty leagues above Tombekbé, and when we should be there, to go with a party of Frenchmen on land to cover our progress on the river of the Chickasaws. In addition to this I had two warriors remain to embark with me in order to send them to them when I should be near Octibia, if I arrived sooner than they. The same even- ing almost all the chiefs began their journeys back to their villages.

On the second we finished unloading the big boats, work that the rains had interrupted, and I had rations distrib- uted to everybody to start out the next day. On the third we set out from Tombekbé and finding the currents not so strong (f. 194 v.) as before I put one of the two Indians on land on the ninth to go and tell the Choctaws that I was expecting to reach Octibia in five days where in fact I arrived on the fourteenth. I spent two days there in drying my provisions without receiving news from the Choctaws although I sent every morning the second Indian from my boat to reconnoiter. On the seventeenth my first courier arrived with two Choctaws and a letter from Sieur de Léry from which I learned that he was on the way with a large party of chiefs and warriors, but that the rain that they had had for nine days in succession had delayed them and that they had been on the point of abandoning the expedi- tion. Sieur de Léry however arrived himself the next day with the chief of the Epitoupougoulas, and he told me that he had left the first parties on the (f. 195) banks of the Octibia where the last would go one day afterward. I decided thereupon to continue my way on the next morning, leaving an interpreter with two pirogues to carry the Choctaws across the Octibia, and in addition to that I gave orders to the company of volunteers com- manded by Mr. Le Sueur to remain to proceed on land with them to the place where we were to disembark as we had agreed. The same evening we arrived at the old portage where the volunteers arrived as soon as we did bringing with them the majority of the chiefs and war- riors, and on the twenty-second we found them all at the new portage where we disembarked about nine leagues from the Chickasaw villages.

On the twenty-third at daybreak I had a number of piles cut and outlined a little fort which was erected at once for the (f. 195 v.) defense of our conveyances. I drew a garrison of twenty men from the companies to remain there under the command of Sieur Vanderek, to- gether with the keeper of the stores, the captains of the boats and several who were sick. I had the time to notice as I looked at all the Choctaws assembled together that they had not come in such great numbers as they had said and that there were scarcely more than six hundred men. I had a great deal of trouble in finding a certain number of them who would carry for hire sacks of powder and sacks of bullets that the negroes could not take since they were already loaded with other things.

On the twenty-fourth after having provisions taken for twelve days I left the portage in the afternoon and camped in the evening two leagues from there. The rains by which I had been so inconvenienced on the river did not leave me at all on the land. Hardly were we encamped when we went (f. 196) through a violent storm that began again several times during the night and which made us all apprehensive for our munitions and our provisions. We succeeded however in preventing them from becom- ing wet.

On the twenty-fifth we had in a space of five short leagues to pass through three deep ravines in which we had water up to our waists. As the banks were covered with very thick canes I had sent a reconnoitering party ahead. After that we saw nothing but the finest country in the world, and we camped at the edge of a prairie two leagues from the villages.

An hour before Red Shoe had come to tell me that he was going scouting with four of his men, and as I feared that he might bring me some false report I had made him consent to take with him Sieur de Léry and Sieur Mon- brun who were there.

(f. 196 v.) The Choctaws not seeing them came back at night and having heard several gunshots fired fell back into their suspicions. They said among themselves that I had sent de Léry with Red Shoe only to have the latter's head crushed and to have some letter carried by the other to the Chickasaws to notify them of my arrival. These rumors, all ill-founded as they were, were about to make them all abandon the expedition when the scouts arrived at daybreak. They told me that they had been attacked by a party of fifteen men who had fired at them from a somewhat great distance, and that in this way we were ourselves discovered.

The Choctaws, quieted by the return of Red Shoe, set out on the march with us. At the first halt the Great Chief came to ask me what village I wished to attack first. I replied to him that I had orders (f. 197) from the King to go first against the Natchez as the authors of the war. He said to me thereupon that he would have wished very much that I might attack Chukafalaya first; that this village which was the first on our way and the nearest to the Choctaws gave them more trouble than all the others; that it was there that he had lost his son and his uncle; and finally that it was there also that we should find a larger store of provisions without which they could not follow us any longer since they had consumed all that they had brought. In spite of the eagerness of the other chiefs to support this sentiment I persisted in my wish to go against the Natchez, not doubting that the Choctaws would return when I had taken this village since it is their custom to flee as soon as they have struck a blow. With the promise that I gave them that when the Natchez were once defeated I would return to (f. 197 v.) Chukafalaya they seemed satisfied, but I soon learned that they had done anything but abandon their design. Their guides after having made us march here and there in the woods as if to lead us to the large prairie where is ihe main part of the Chickasaw and Natchez villages led us at last to a prairie which is possibly a league in circumference in the middle of which we saw three small villages situated in a triangle on the crest of a hill at the foot of which an al- most dry stream was flowing. This small prairie is only a league distant from the large one and is separated from it by a wood. The Choctaws came to tell me that we should not find any water further on, and I made them march along the little wood that borders the prairie in order to reach a small height on which I made them halt to take food. It was then past noon.

However the Choctaws, who wished at any (f. 197 re- peated) price whatsoever to enter into an action with these first villages, went and skirmished there as soon as we had entered the prairie in order to draw the enemy's fire upon us, in which they succeeded so that the majority of the officers joined the Choctaw chiefs to ask them to attack these villages in which they did not think that we should find great resistance.

Pressed on all sides not to leave these forts behind us and not being able, so to speak, to do so without rebuffing the Choctaws I had the chiefs assemble and I again made them promise that they would follow me against the Natchez after the capture of these three villages. This they did with great protestations, reiterating to me that they no longer had any provisions, that they would find themselves forced to abandon us if we began with the Natchez who were very poor in provisions, whereas these villages ordinarily had (f. 197 repeated) more than all the others of the nation together. I surrendered therefore to their arguments, or rather to the necessity of submit- ting to what they wished, and I ordered for two o'clock in the afternoon the company of grenadiers, a detachment of fifteen men from each of the eight French companies, sixty Swiss and forty-five volunteers and militiamen, un- der the command of Chevalier de Noyan.

During our halt the Choctaws informed me that the reinforcements from the villages of the great prairie were appearing and that there were many warriors. I had them take arms to receive them, but the Choctaws having attacked first and killed two chiefs whose scalps and standard of feathers they brought me, the rest scattered from the place where we had stopped at a rifle shot from the villages. We distinguished there some Englishmen who were making great efforts to prepare the Chickasaws to withstand our (f. 198) attack. In spite of the irregu- larity of this conduct, as at our arrival they had in one of the three villages raised an English flag to make them- selves recognized. I directed Chevalier de Noyan to pre- vent any one from attacking them if they wished to re- treat, and to afford them leisure to do so I ordered him to attack first the village opposite to that with the flag. In the meanwhile the detachment under orders began to march and reached the hill under the protection of several mantlets, which to tell the truth were not of use long because the negroes who were to carry them to a certain place, having had one of their men killed and an- other wounded, threw down the mantlets on the spot and ran away. On entering the village called Ackia the head of the column and the grenadiers were exposed and were very badly handled. Chevalier de Contrecoeur was killed there (f. 198 v.) and a number of soldiers were killed and wounded. However they captured and burned the first three fortified cabins and several small ones that defended them, but when the time came to pass from those to others Chevalier de Noyan found that he had with him almost nobody except the officers of the head of the column, a few grenadiers and about a dozen volunteers. The death of Mr. De Lusser who was killed in going across as well as that of the sergeant of the grenadiers and of part of his men had already frightened the troops. The soldiers crowded together behind the cabins that had been captured without the rearguard officers being able to re- move them from them, so that the officers of the head of the column were almost all disabled. In one moment Chevalier de Noyan, Mr. De Hauterive, the captain of the grenadiers, Sieurs Velle, Grondel,i and Monbrun were wounded. It was in vain that Chevalier de Noyan, wish- ing to hold his ground, (f. 199) sent Sieur de Juzan, his adjutant, to try to bring up the soldiers. This officer hav- ing been killed beside them only increased their terror by his death. Finally the wound of Noyan having obliged him to have himself taken back behind a cabin, he des- patched my secretary, who had followed him, to me or- dering him to repori to me the distressing situation he was in and to warn me that if I did not have the retreat sounded or did not send reinforcements soon, the rest of the officers would soon meet with the fate of the first; as for himself he did not yet wish to have himself carried off for fear that the few men who remained might seize the opportunity to leave helter-skelter; that besides there were fully sixty or seventy men killed and wounded. At this report and inasmuch as I myself saw from where I was the troops (f. 199 v.) both French and Swiss falling back, and further because we had just had a new alarm in the direction of the great prairie and because we were all under arms, I sent Mr. De Beauchamp with eighty men to have the retreat carried out and to bring off our dead and wounded, which was not done without losing several more men. Sieur Favrot was wounded in it. When Mr. De Beauchamp arrived at the place of the attack he found almost no soldiers there any longer. The officers united and abandoned were holding their ground, that is to say that they were at the cabin nearest to the fort. Mr. De Beauchamp made them retire and went to the camp in good order, the enemies not having dared to come out to charge him. It is true that the Choctaws, who until that time had kept themselves under cover on the slope of the hill waiting for the outcome, then rose and fired (f. 200) several volleys. They had on this occasion twenty-two men killed and wounded, and this eventually contributed no little to disgust them.

My lord will see better by the map enclosed herewith the situation of the three villages and the disposition of our attack. What may be added about the method of these Indians in fortifying themselves is that after hav- ing surrounded their cabins with several rows of large piles they dig holes in the ground inside in order to hide themselves in them up to their shoulders, and they fire through loopholes that they make almost flush with the ground, but they derive even greater advantage from the natural situation of their cabins which are separated from each other and all the shots from which cross each other than from all that the art of the English can suggest to them to make them strong (f. 200 v.). The covering of these cabins is a wall of earth and wood proof against burning arrows and grenades so that nothing but bombs can harm them. Now we had neither cannons nor mor- tars. Besides I no longer doubted when I saw the large number of our wounded that I should be obliged to aban- don the expedition on account of the difficulty of trans- porting them, and in fact there was no other course to be followed. I was afraid that the famished Choctaws might leave us, in which case we should have been harassed in the wood and attacked while crossing the ravines where we should have lost many men. What justified my fear was that in spite of all that I could say to them it was necessary to share our provisions with them in order to make them promise to come with us.

On the next morning, the twenty-seventh of May, I had little stretchers made to carry our wounded (f. 201) and at one o'clock in the afternoon we set out in two columns as we had come. Our soldiers fatigued and loaded with their baggage had very great difficulty in carrying the wounded and we marched until evening in order to go and sleep at a distance of a league and a half in the wood. This march completely disgusted the Choctaws. Red Shoe and several others did everything in their power in order that their people might abandon us. I overlooked nothing to frustrate this movement. I talked on arriving to the Great Chief, to the chief of the Chick- asawhays and to several others, calling their attention to the fact that it was to please them and to avenge them that I had attacked the Chickasaws, my plan being to go against the Natchez; that in view of this they ought not to abandon people who had been active for them. They (f. 201 v.) admitted this to an extent, but they alleged that our wounded were delaying our march too much, where- upon I decided to propose to them to have them carried by their warriors. After many difficulties they agreed to carry one per village. Alibamon Mingo gave the example by having my nephew De Noyan carried by his men, and as we thereby had more people to relieve each other to carry those whom the Choctaws did not take we arrived at the portage on the twenty-ninth, having lost on the way two men who died of their wounds.

We reembarked on the same day and we found the river so low, although we had been away only five days, that we were obliged to cut trees and work in several places in order to obtain passage for our boats (f. 202). It was then that I recognized even better than before that the plan that I had adopted was the only one to adopt, for if in fact we had been absent four days longer, we should perhaps have been obliged to return by land and to burn our boats.

Three leagues above Tombekbé where I arrived on the second of June I noticed a recently traced trail of the English and I found a pirogue that I set adrift. Sieur de Léry, whom I sent ahead to the Choctaws to learn news of them, reported to me that they had come with twelve horses loaded with cloth and that they had done their trading, after which they had gone back home. As soon as possible I sent from Tombekbé the wounded with the surgeons, and on departing on the third I left Mr. De Berthet, a captain, to succeed Mr. De Lusser with a (f. 202 v.) garrison of thirty Frenchmen and twenty Swiss. I left him provisions for this entire year and goods in the warehouse for trading. I also left him the contracts for the construction of the fort with orders to have work done at once on the ground that I had outlined. On the seventh I arrived at the Tohomes where I learned from an Indian the first news of the disaster of Mr. D'Artaguette which Mr. Diron confirmed for me on my arrival the next day at Mobile. In another letter I shall have the honor of reporting the sad circumstances to your Lordship. I left Mobile on the fifteenth and ar- rived here on the twenty-second where I did not find the King's ship which had already left for the Balize whither I am sending my packets.

(f. 203) Your Lordship will have seen by this narrative of the most difficult campaign in the world that in the plan, in the execution and in the retreat I used all the means imaginable, and you will also have noticed that after having met with a slowness in the preparations that I could not have anticipated I was still less able to fore- see the cowardice of the troops that I had under my or- ders. It is true that when one considers the wretched blackguards that are sent here as recruits one ought never to flatter oneself that one will make soldiers of them. The unfortunate thing is to be obliged with such troops to compromise the honor of the nation and to expose officers to the necessity of getting themselves killed or of dishonoring themselves. The recruits that came on the Gironde are even worse than the preceding ones. There are only one or two men more than (f. 203 v.) five feet in height. The rest are below four feet ten inches. As for their sentiments I can add that of their number of fifty-two more than half have already been flogged through the lines for theft. In short they are useless mouths living on the provisions of the colony which will derive no service from them.

The retreat which I have had carried out without any loss is the only thing with which I am satisfied since I have brought back a good number of honorable men who are to be reserved for another occasion. After that I shall esteem myself happy if my lord will kindly do justice to my efforts and to my zeal for the service.

I am with a profound respect,

My Lord,

Your very humble and obedient servant,

Bienville.

At New Orleans,

June 28th, 1736.

In order the issues follow: beginning with Sieur DuCoder's loss of the powder to the Chickasaw, the tardiness of the salt provisions and mortars on the King's vessel, as of January 15th the boats' (bateaux) contractors were 3 months late, the artillery mortars were not on the King's vessel, a boat with rice lost half of its cargo, without rice biscuits were needed to feed army so bakers were sent to Tombekbe and orders sent for ovens to be built, after Bienville arrived at Tombekbe he discovers only one oven built. There are two principal issues: First, the construction of boats to convey troops and materials was late. How can the contactors be this late? This is the first correspondence mentioning the tardiness of the boat contractors. Second, without the mortars how would Bienville destroy the Chickasaw and Natchez forts? He knew that cannon had been used against the Natchez forts without effect. The mortars were needed to send shells over the fort walls. With just one of these principal issues, the entire campaign should have been called off. But it was not.

I find something very interesting about the Second Correspondence. Note it is dated June 28, 1736 after the southern force battle with the Chickasaw. I am focused on all of Bienville's issues. Did Bienville have other correspondences with Maurepas before his departure from New Orleans i.e. before the campaign was in motion? And, if there are any correspondences, did Bienville mention any of these issues? There are two correspondences: the first is dated February 3, 1736 (MPA I 274) and it is from Salmon and Bienville in New Orleans to Maurepas. No mention of any of these issues was made! In the second correspondence dated February 10, 1736 (MPA I 276) Bienville in a lengthy letter mentions on page 293 a letter from P. D'Artaguiette stating his concerns getting the Illinois Indians late to leave on a raid against the Chickasaw. On page 294 he provides Maurepas with a confusing, rambling out-of order confession that he will not meet P. D'Artaguiette at Ecorse a Prudhomme in the middle of March! At first he writes, "If I had been able to attain a junction with the Illinois forces, I should have been able to promise myself complete success in this enterprise. Mr. D'Artaguette is in a position to put three hundred brave and robust Frenchmen in arms who would have been great assistance to me. I had sent him orders to do so, and I have made an appointment with him for the tenth or the fifteenth of March at the Prudhomme Bluffs which are only four days journey from the Chickasaws." And it's the boat builders' fault, "but the settlers who had contracted for the conveyances … have been so slow in furnishing them… I do not foresee that I shall be able to leave Mobile before the fifteenth of next month." Bienville does not mention a second or final order to Pierre D'Artaguiette. So Bienville is telling Maurepas that he will not meet Pierre D'Artaguiette at Ecorse a Prudhomme in mid March. He will not have a coordinated attack on the Chickasaw. He does not mention the lack of mortars.

Why in the Second Correspondence above did he tell Maurepas, "the boats that I had ordered for the month of October had not been furnished by the contractors on the fifteenth of January. I left at once for the capital in spite of the inclemency of the season. I despatched on arriving there a second courier to Mr. D'Artaguette to order him to delay his departure from the Illinois until the end of April." Here he has written Maurepas that when he discovered that the boats were three months late, he rushed back to New Orleans to send Pierre D'Artaguiette final orders relative to their meeting. Why the rush back to New Orleans? Bienville knew at the time of year the Mississippi River current and weather would prove difficult for his couriers to reach P. D'Artaguiette in two months, if he were at Ecorse a Prudhomme, and longer if he were at Fort Chartres. We know that there were final orders that barely reached P. D'Artaguiette. Why didn't Bienville mention to Maurepas that he planned to send final orders? Is there a missing correspondence?

In Fourth Musing we noted there are two versions of Bienville's final order to Pierre D'Artaguiette. Bienville in his Official Account stated it was "to take his measures accordingly" MPA I 312; however, in the Unknown Account the acting commandant at Fort Chartres de la Buissonneire and his principal clerk Delaloere wrote separate letters that stated that the final order was "to retard his march, and wait for him in order that they might strike together against the Chickasaws and Natchez," see Fourth Musing Indiana Historical Society Indiana's First War. Page 121.

In the three paragraphs above I have underlined the four accounts (that I am aware) of the second or final orders from Bienville to Pierre D'Artaguiette. Surely Maurepas was dizzy trying to sort out Bienville's lies, for the lack of a better word.

Let's return to the Second Correspondence…

I wonder … where is Bienville's journal? Does MDOH possess a copy? Is it available? Would the journal reveal the truth about when Bienville knew about the boat contractors' lateness? OR Would the journal reveal what the final orders were to Pierre D'Artaguiette?

Also in the Second Correspondence, Bienville reminded Maurepas about "the blow struck at Sieur Ducoder by the Chickasaws"…that narrative was covered in Fourth Musing and refered to the Chickasaw capture of 1700 pounds of powder on the Mississippi River which was intended for Fort Chartres and P. D'Artaguiette's campaign. Instead the powder was used against P. D'Artaguiette and Bienville.

Sieur duCoder was Pierre Laurent Ducoder an ensign at the time of the Mississippi River powder loss and his capture by the Chickasaw. He escaped from the Chickasaw and reached Mobile prior to Bienville leaving on the Chickasaw campaign.

Mr. de Lusser was Joseph Christophe de Lusser a Swiss born Captain of Infantry. Sieur de Lusser traveled among the Choctaw villages and recorded a journal which is included in MPA I 81. Bienville ordered him to establish the post at Tombekbe.

Sieur de Hauterive was Renaud Bernard D'Hauterive who came to Louisiana in 1719 from Tours, France and assumed command at the Natchitoches and later participated in the Natchez War. He was born in 1691 and achieved the rank of Captain at the time of the French/Chickasaw War of 1736. He became Major Commandant of New Orleans in 1738 and participated in the French/Chickasaw War of 1739 as a member of the Council of War. He was awarded Chevalier de St. Louis and died 1743. He accumulated land and slaves. The French Engineer and map maker Ignace Francois Broutin purchased his plantation.

Sieur de Lery was Joseph Chauvin de Lery 1674-1738 who was a Creole per Bienville MPA I 279. He was born in Montreal and died surveying the Yazoo River for possible use in the next Chickasaw campaign, see MPA I 361. He served as a militia captain and Choctaw trader. Bienville had him trading and collecting information in the Choctaw villages almost constantly 1734-1736.

Jean Paul le Sueur was an Infantry Captain. He led a very successful campaign against the Natchez. He also led attacks against the Chickasaw after the Chickasaw Wars in which he participated as Captain of the Militia. He was a cousin of Bienville through his mother.

Chevalier de Noyan was in charge of Bienville's Chickasaw southern campaign. He was Pierre-Benoit Payen de Noyan and a nephew of Bienville's. He was assistant adjutant at Mobile and Fort Conde. His brother was Gilles-Augustin Payen de Noyan who served as King's Lieutenant in New Orleans.

Chevalier de Contrecoeur was Antoine de Contrecoeur the son of Francois Antoine Pecaudy de Contrecoeur and Jeanne Saint Ours. He was a product of a famous military family on his father's side.

Mr. De Beauchamp was Jean Jardet de Beauchamp (sometimes spelled Bauchamp) 1694-1754. He was King's Lieutenant, Major and Commandant Mobile. He was critical of Governor Perier, whom Bienville replaced.

Grondel was Jean Philippe Gaujon de Grondel. His Chickasaw wounds healed, and he had a long military career. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Philippe_Goujon_de_Grondel

Volant was Jean Gregoire Volant a Swiss from Basil. At the battle he was a lieutenant and Commandant Swiss troops at Mobile. He moved to Louisiana in 1731.

Octibia is a creek shown on de Cresnay map of 1733 link. It is labeled "Ruisseau Octebia" located on the "Riviere Des Chichachas". It is Tibbee Creek south of West Point, MS.

To Bienville the "capital" was New Orleans.

The Choctaw village of Chickasawhay was also spelled Chicachae or Chikachoe MPA I 116,143. It is spelled "Chicachae" on de Cresnay map.

"Tohomes" or Tohome was a Choctaw village north of Mobile bay on the Mobile River. Also spelled Tomes MPA I 117 and "Thome" on the de Cresnay map.

The Choctaw chiefs that met Bienville at Tombekbe were the Great Chief, who was the Great Chief of the Choctaw Nation by birthright. He lived at Couechitto village; Alibamon Mingo who was a Great Medal Chief and lived at Concha; Red Shoe was a war chief who fought the Natchez, see MPA I 188, and also conducted raids against the Chickasaw, see MPA I 159 and 187. The French, particularly Governor Bienville, accused him of sponsoring English traders and trade among the Choctaw. He did. He appeared to the French to play both sides-English and French. He did. He stated via interpreter that his desire was to have French and English trade available to the Choctaw people, MPA I 271 "This is the way to lack nothing". He lived at Cushtusha. In my opinion his actions represented his people. From the Choctaw point of view, the French compared to the English had cheaper goods particularly cloth and guns. This mattered to the Choctaw as they had a population 5 to 6 times the Chickasaw with little area to hunt. They were surrounded by other Nations. And the deer hides from the pine barrens that dominated their hunting grounds were small. Red Shoes was a fresh voice who spoke for the benefit of his people. In my opinion he should have a statue erected in his honor.

Bienville in 1736 was 56 years of age and suffered from sciatica. In fact, the biographical link of Bienville indicated he was bed ridden from the disease in 1738-9. I can only comment that sitting for hours in a boat days on end in the elements as Bienville did would not be kind to his age or health.

It is interesting that the Choctaw at Camp Tombekbe and later near the Chickasaw villages suggested to the French that the French real plan for the campaigns was to eliminate the Choctaw. The Choctaw had met in Mobile with the French in December 1735 to receive their annual presents where Bienville told them his campaign plans against the Chickasaw. When did the Choctaw develop such distrust of the French? And where? English traders?